I recently had a chat with José Cerca about his recent piece in Molecular Ecology about how we define parallel and convergent evolution. Questions are in bold.

What got you interested in this topic?

I was always fascinated by how the environments drive evolutionary change, and parallel/convergent evolution are really fascinating as they allow us noticing natural selection and seeing what just keeps evolving across the tree of life.

Great! This paper obviously stems from getting tangled on the various definitions of parallel v. convergent evolution. Was there a project in particular that got you thinking along these lines?

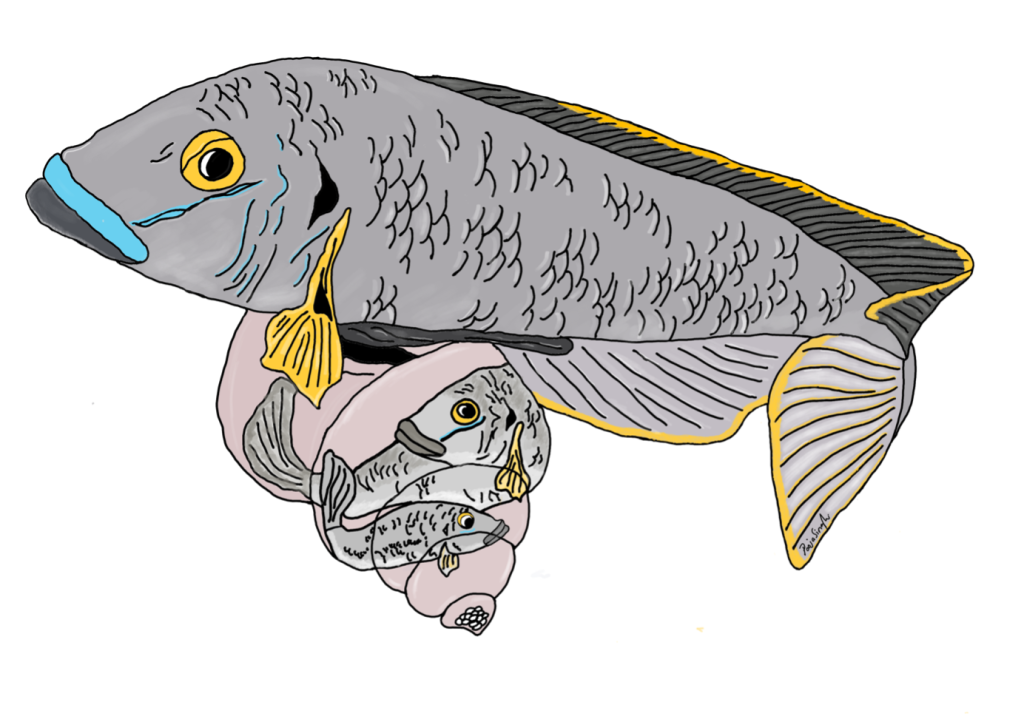

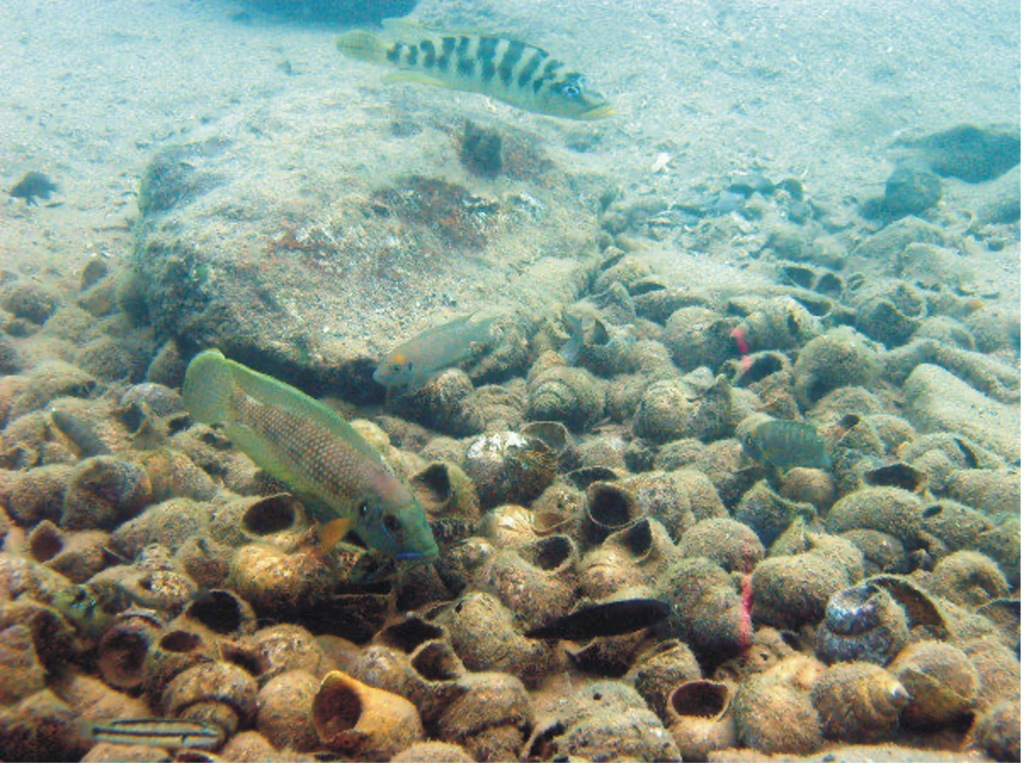

Yeah! So this goes back to another MolEcol paper, which I co-first-authored with Will Sowersby ( https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/mec.16139). Will and his team were focusing on the midas’ cichlid fishes, where these thick lips (Amphilophus labiatus) were present in two different lakes. Will is an ecologist, and his data clearly showed that the A. labiatus had significantly different lips and diet than other species in the lake, A. citrinelus. When I did the genomics of the system … it was quite a mess to untangle. The PCA showed some geographical segregation of PC1 and a weak’ish species segregation on PC2 – so both A. citrinelus and A. labiatus were segregating on PC2 let’s say, ‘in parallel’. This was a mess and we had hybridization across the board, and a lot of phylogenetic mess. So when it was time to write the paper, we entered this rabbit hole: is it parallel? Is it not? In the end we said it wasn’t. A collaborator, David Marques, wrote to me personally saying that, for him, that was clearly parallel evolution … and this made me want to read up the literature and find a good answer (spoilers – I ended up agreeing with David!)

That’s pretty relatable! That’s an anxiety that we all share, right – that some one we look up to will point out a flaw in our work after publication. Even though it is nerve wracking, it is clearly constructive – it certainly has been in this case!

Yeah! Regarding flaws … One thing I liked about the ‘eLife experiment’ is seeing papers as ‘not writen in stone’. Papers can have mistakes, as long they’re not ‘unscientific’.… But ultimately, it’s always nerve wracking.

The paper largely deals with semantics, which terms to use and when. Do you think semantics are particularly important?

Yes. Totally. I think semantics are important; two reasons: first, as we diversity science. As a non-native speaker I regularly have to be constantly checking nuances on terms. Second, I think many times we could avoid unproductive discussions if we agreed our definitions are just not the same. Semantics is this thing that allows us to see whether we disagree in the mechanisms/interpretations, or just in the way we define things. I learnt this in a debating competition: sometimes just nailing down the definition of a term gets us really much further. One word I think a lot about semantics is respect: does ‘I respect that!’ mean you tolerate something, or that you look up to that? I am not really certain and I am sure if you ask different people from different social backgrounds/countries/first-languages, you’ll get different answers.

I agree with you – even if sometimes arguments around semantics can be quite draining! The argument around parallel/convergence probably gets repeated fairly often.

I really hope the paper makes a strong argument to stopping these discussions and that we can all get behind repeated evolution. As I went through different cases I kept thinking: it doesn’t matter whether we call this parallel/convergent evolution, as long as we recognize it repeatedly happens. An alternative – not explored in the paper, and which is messier – is encouraging people to state their definition of parallel/convergent on their paper introductions. But again, this will keep the mess.

I kept getting back to the cichlid work of Claudius Kratochwil. He has these elegant (natural) experiments on transposable element (TE) evolution in cichlids and I kept thinking … it’s kinda cool things just re-evolve and how his work shows the genomic basis of all these things, but perhaps we do not even care for the initial phenotype. For instance, the evolution of melanic stripes in fishes – does it really matter if before selection there were circles, or no melanin at all? Perhaps that may be cool for someone interested in phenotypes, but if your question is on molecular mechanisms – not so much; and so, you can just call it repeated evolution of stripes and move on.

Yeah, I think that would get messy! In the paper, you talk about “gene reuse” as opposed to parallel/convergent evolution. So that’s a kind of catch all. Do you think it matters that population genetic studies may not be looking at phenotypes at all?

I just really think that things get really messy at the genetic level. I kept going through this examples that are on the paper, say – if a phenotype re-evolves from different paralogs, that are 99.9% similar. Is it parallel? Is it convergent? It’s just a rabbit hole. Where do you draw the line? In the end, and mostly due to the extremely helpful review of Maddie James and editorial work of Loren Rieseberg, I just went and got gene reuse, and went for: let’s just circumscribe parallel/convergent evolution to the phenotype. I really think it became a more robust framework because of that – but I also expect that to ruffle the feathers of molecularly oriented people 🙂

I got the gene reuse umbrella from a really cool paper from some colleagues of yours in BC (https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2012.2146) [TB is based at UBC in Vancouver]

Right, but what if you looked at some signal of selection (e.g. sweep signals or something like that) and find patterns in homologous regions. At the phenotype perhaps there have been anti-collinear trajectories, to use your term. Does that matter?

I think the terms collinear/confluent are not mutually exclusive with convergent/parallel evolution – they just explore different dimensions: the first on how phenotypes are evolving and the latter about observed/end points.

If you find signal of selections, and experimentally validate them (we don’t do this enough in evolutionary biology, given how convenient genomics became), and find patterns in homologous genes, you can just say – hey I have parallel evolution (if you show ancestral phenotypes to be the same) with gene reuse at homologous genes. Does it make sense?

Yes, I think so. Ok, last question: What was the hardest part about this project?

There were two particular aspects. First, the semantic, because I noticed sometimes I’d send the manuscript to people and they’d be put off by statements which to me were very reasonable. When I asked them about what they meant and we sat and chatted – it ended up being about semantics (of simple things – such as similarity). Second, it was putting the framework together. If you see the acknowledgements (big shoutout to everyone there), people kept coming up with holes and with exceptions which sometimes made me have to revamp the whole thing.

Cerca, J. (2023). Understanding natural selection and similarity: Convergent, parallel and repeated evolution. Molecular Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17132